When the NBA Entered 'The Big Time'

Magic Johnson and Larry Bird are only part of the story

Pro basketball was supposed to become “the sport of the ‘70s,” according to the hype of the time. It most definitely did not.

But the NBA’s eventual rise was born of events in that decade, as recounted by Michael MacCambridge in his latest book, The Big Time: How the 1970s Transformed Sports in America.

Michael is the author of seven books and a 5x5 subscriber. So I reached out to tap into his deep understanding of what the 1970s meant in sports, particularly the NBA and the ABA.

Here’s our exchange via email:

Royce: The book is backloaded with NBA content. Is it your view that the more compelling parts of the NBA decade came in the latter half of the '70s?

Michael: The NBA was fascinating throughout the ’70s. But the nature of this book — which was always meant to be a broad social history encompassing American sports throughout the decade — dictated that I had to pick my spots.

Certain events that carried a lot of cultural relevance, like the first Ali-Frazier fight or Henry Aaron breaking Babe Ruth’s home run record, earned more sustained attention, while other objectively “big” events — the Dolphins going unbeaten in 1972, Secretariat winning the Triple Crown in 1973 — received less coverage, because they fit less seamlessly into the themes I was pursuing, and the larger story I wanted to tell.

With the NBA, I wanted to evoke the somewhat low-rent nature of the entire enterprise in the early ’70s, with examples like the Knicks having to wash their own uniforms on the road, or the National Anthem being played on a cassette recorder at Chicago Stadium, or Oscar Robertson’s typical pregame meal being two hot dogs and a Coke an hour before tipoff.

Later in the book, to your point, I spent more time on the NBA-ABA merger (which David Stern always insisted was an expansion) and then that confluence of changes at the end of the decade that signaled a pro basketball renaissance — the three-point line (even though it was sparingly used at first), the arrival of Magic Johnson and Larry Bird, and the NBA becoming the first league with a national cable TV contract. Those things felt very relevant to where the game is today, in a way that, for instance, the Warriors sweeping the Bullets in the 1975 Finals did not.

Royce: We know about Magic and Larry, and you cover their emergence, particularly in the 1979 NCAA title game. What else drove the NBA’s turnaround?

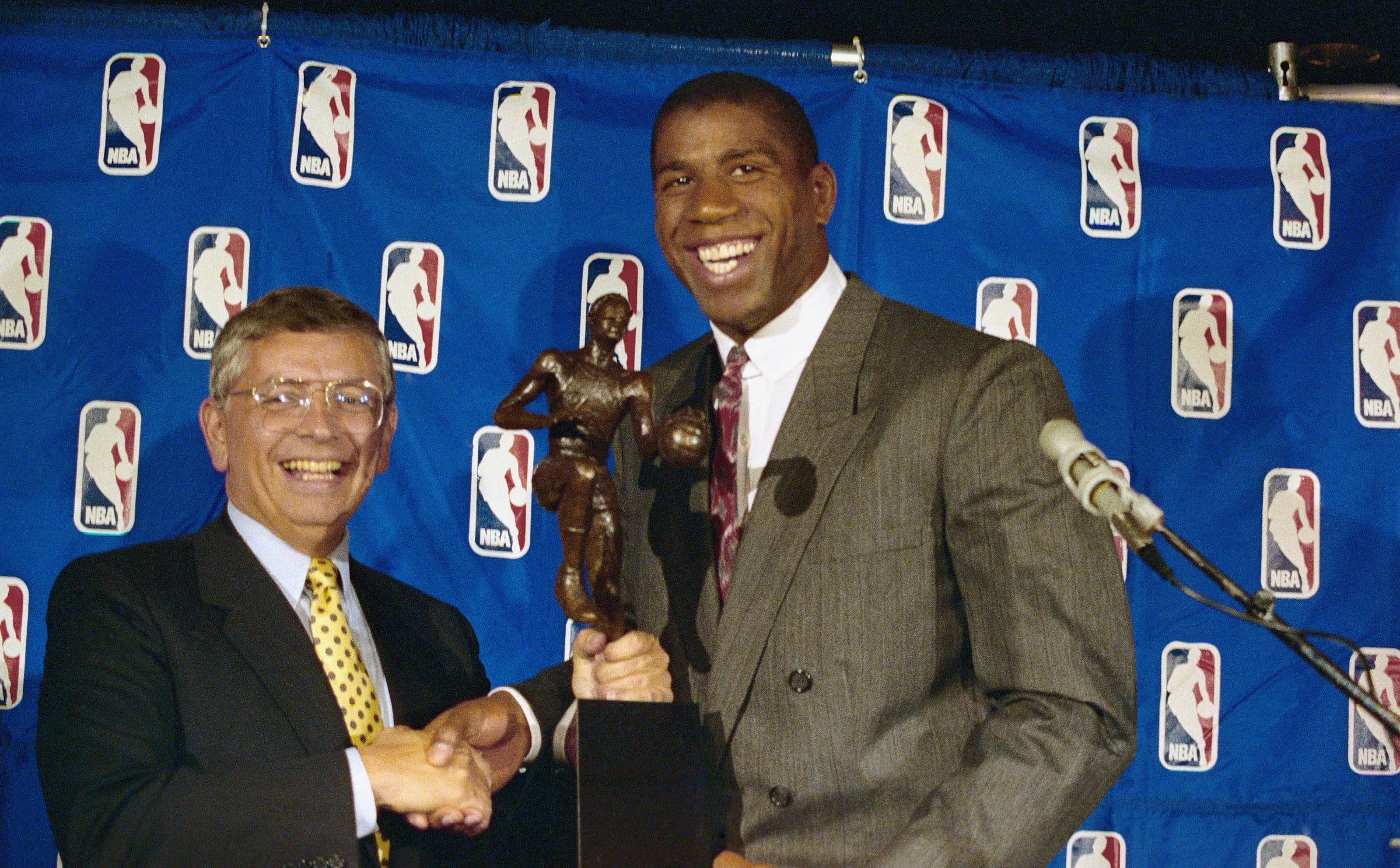

Michael: The obvious answer is the genius obsessive David Stern, who even by the end of the ’70s was setting the agenda at the NBA offices and at some level “running” the league, even though Larry O’Brien was still nominally the commissioner.

Stern, like Pete Rozelle before him, was a detail-oriented micromanager who understood the importance of competitive balance was in giving fans in every city a sense of hope. Stern’s work with Larry Fleisher in coming up with the salary cap was a landmark moment in the history of American sports. This is something that the NBA and the NFL (and the NHL and MLS, for that matter) still do so much better than Major League Baseball.

Beyond that, of course, the league got fortunate. Magic Johnson was perfect for L.A., and Larry Bird was ideal for Boston. That epic rivalry between the Celtics and Lakers was crucial.

Moving into the Eighties, I’ve also always thought there was something important about the way Pat Riley emerged as a personality as the NBA was growing in popularity. There were certainly other basketball coaches who were intentionally “stylish” — Al Attles in a leisure suit and Larry Brown in disco-era overalls in the mid-’70s come to mind — but Riley was the first coach that I remember rocking Armani suits courtside, who looked at once modern and sophisticated. There was no real analogue for that in football at the time; Tom Landry and Hank Stram had both been clothes horses, but they would have looked absurd on Miami Vice. Pat Riley fit right in with that moment in history.

Royce: What was your favorite NBA section to work on? And the most difficult?

Michael: One and the same. The circumstances surrounding the merger between the NBA and ABA were endlessly fascinating, and also maddeningly difficult. As with the NFL and AFL in the Sixties, there were ongoing back-channel negotiations, and there were times when a full merger of nearly all the ABA teams was on the table.

But the future of any possible merger was tied up with Oscar Robertson’s lawsuit against the NBA,1 and the outcome of that was inextricably connected to the owners and players coming up with a collective bargaining agreement that offered players some measure of free agency and autonomy. In that thicket of political machinations and business dealings was the path to the future of American sports.

Royce: These days, the NBA is bigger than baseball by most measures. Would that have seemed possible in 1979?

Michael: I want to say that like a lot of other things that happened in the late ‘70s — the rise of college basketball, the dawn of analytics in sports, the birth of ESPN — you could squint and see the broad contours of the future.

What we start to see in the ’70s is sports more intentionally intersecting with popular culture. Think of the early days of rap — Kurtis Blow’s “Basketball” was one obvious connection. Even back then, not a lot of rap songs were name-checking baseball players, if you know what I mean.

I still love baseball, but if I’m honest, I spend a lot more time watching football, soccer and basketball than I do watching baseball.

Even in the late ’70s, basketball and football had built-in advantages over baseball. Because of the popularity of college football and college basketball, you knew the players who were coming into the NBA and the NFL. Even with the College World Series now a TV staple, that’s much less the case in baseball than the other sports.

Before being settled in 1976, with David Stern negotiating on the NBA’s behalf, Robertson’s 1970 lawsuit prevented the merger. The settlement allowed the merger to proceed and created the NBA’s free agency system.

This was really inciteful. As a 2000s baby, and someone who only got into the NBA during the early 2010s, my NBA history is not the greatest, so this was a really compelling read.

Fascinating stuff, Royce & Michael! Thanks!